The local chronicle, history, cinema, and nightlife: the glorious past of the Amalfi Coast captured by the famous photographer from Amalfi

February 3rd, 2022. By Vito Pinto

Looking at the publication “Amalfi in the ’50s and 60’s – Alfonso Fusco photographer”, the catalog of the homonymous exhibition in Amalfi, one would think that the curator Claudia Bonasi, journalist, would have taken into due consideration what Carlo Bertelli, art historian, superintendent in Milan and former director of the national photographic cabinet from 1963 to 1973, a period during which he encouraged the study and collection of photography as a historical document, wrote.

The attentive director used to say, “photography gives testimony even when it would like to be only descriptive.” A sentence fitting to the valuable work of Bonasi, realized thanks to Antonio Dura, publisher, and director of “Pura Cultura.”

The patronage of the Municipality of Amalfi, selecting photographic images taken in a decade by Alfonso Fusco, a photographer active in Amalfi between the ’50s and ’60s of the last century, and put on display at the Arsenals of the Ancient Maritime Republic (on view until February 28, 2022) “one of the most interesting events of 2021” as defined by Daniele Milano, mayor of Amalfi.

Everyday life after the second world war

There are more than two hundred images, chosen from a family archive that holds more than two thousand, that the publisher Dura did not want to modify, choosing to respect “the framing, the light, the contrasts sought by Alfonso Fusco, so that there would be an exact representation of what the author had portrayed.”

And it was the everyday life of an Italy that had just come out of the tragedy of World War II and was trying to rebuild its houses, work, and life. Intense gazes, those of the people of Amalfi, intent only on recovering from a disaster, on regaining a local and national identity.

In that tiring everyday life are the faces of grandparents, parents, relatives, and friends. Participation in processions, celebrations, citizens, or private events such as weddings. There is a path of life that has laid the foundation for today’s everyday life.

Strong is, in those shots, “the author’s ability – writes Antonio Dura – to portray more than representing people and atmospheres from that world and project them to other worlds and looks unknown to him, like the one from which we observe today.”

Narration as a chronicle

There are also the photos of the “dolce vita” in this bend of the Gulf of Salerno, images that characterized a decade, where above all, it appeared clear the road that the Diva Costa, its inhabitants, had taken and that, perhaps, they knew how to do better than any other profession: tourism. They were the years in which they arrived, almost the heirs of those travelers of the Grand Tour, the first characters attracted by the hospitality that can well be defined as “innate,” which was the foundation of an entire coastal economy.

Vincenzo Esposito, professor of Cultural Anthropology, underlines: “Fusco’s photos could tell something else, beyond what they represent, if only to know fragments of the life of the people photographed, or social situations, or anecdotes linked to the places and, why not, to the things portrayed. And one can imagine kinships, friendships, emotional ties, rivalries, dreams, hopes, disappointments”.

In practice. It is a whole world that contains personal stories, which are inserted into a broader history of the city, territory, and nation. “A narrative – adds Esposito – understood as a chronicle that extends to include other elements, but all only partially significant.”

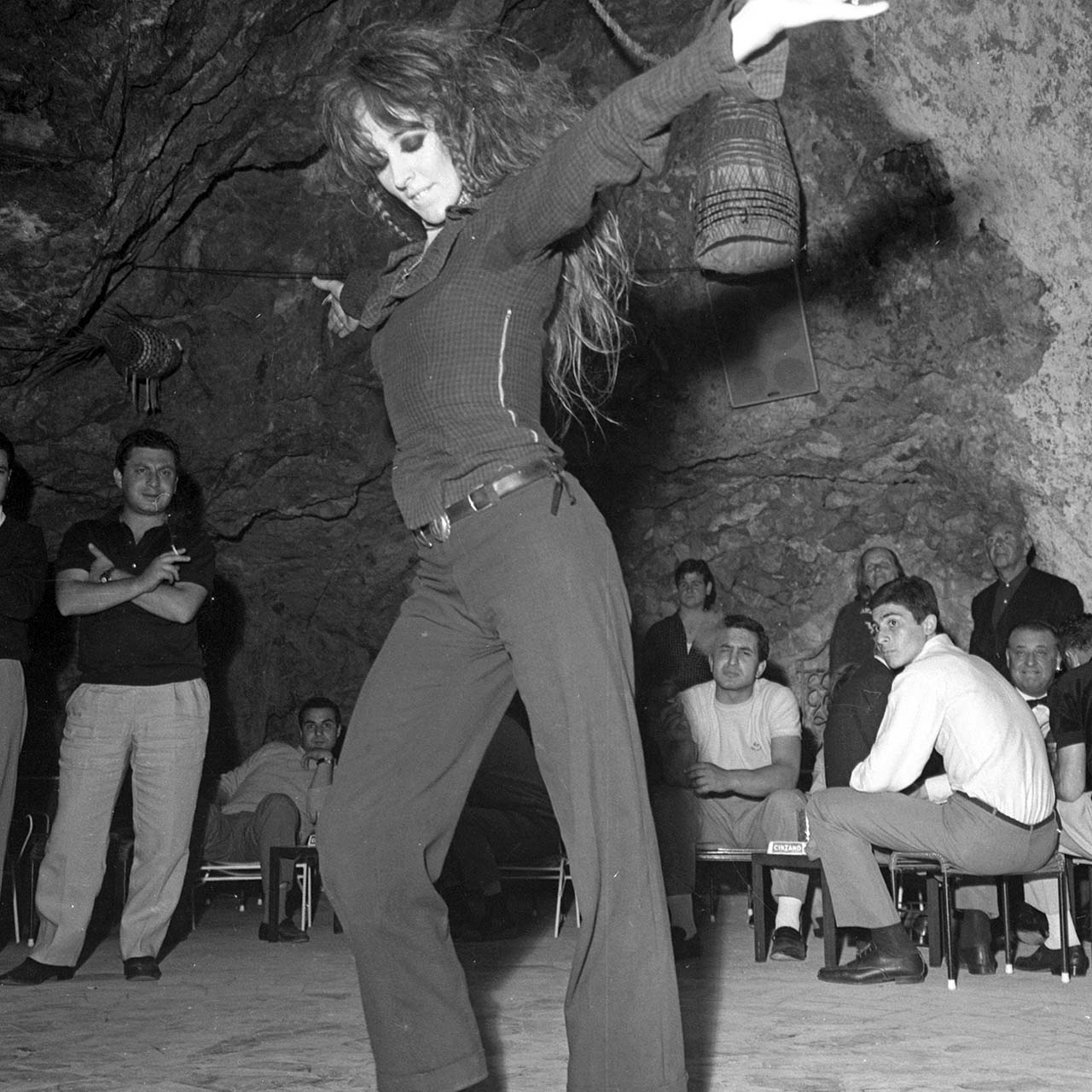

From the movie stars to the legendary nights at the Africana

Those years, portrayed by Fusco, were years of a “reawakening” of vitality, of “Lions in the sun” by Vittorio Caprioli in his directorial debut, of the “campers” who arrived in the evening on board the Vespa Piaggio that became legendary in “Roman Holiday” with Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn, or the 750 motorbikes by Innocenti, and invaded the dance halls where Peppino Di Capri performed his “Twist Again,” Fred Bongusto with “A Roundabout by the Sea.”

In the legendary nights at the Africana, invented by Luca Milano, ballets and colored musicians performed, Valy Myers, the last existentialist of the Coast and muse of Tennessee Williams, danced barefoot, as did Jacqueline Kennedy with the young Agnelli family scion, infuriating the more discerning Avvocato Giovanni. Queen Juliana of Holland and her august consort dined there romantically outside the protocol.

The mayor of Amalfi was Giovanni Amendola, while the Archbishop was Monsignor Angelo Rossini, present in the images of Alfonso Fusco, who did not miss the opportunities to photograph those characters who, in the end, have marked an era that of wanting at all costs and rightly forget a sad period of our history.

Local culture, memories, and history

Esposito remembers that Fusco’s photographs “converse with each other, with the local chronicle, with memories, and with history.” So the FIAT 600 of the then Public Security makes a fine show at the foot of the monumental steps of the Cathedral, and the legendary giardinetta tells of its use for work and family.

There is also the bird seller or the bombardino player of the civic music band and the petrol pump in Piazza Flavio Gioia of Shell, the company of the yellow shell, where the racing car refuels, reminding us of the Amalfi-Agerola hill climb, invented and organized by the then President of ACI Salerno, Renato Palumbo.

The past, a contemporary tale

Alfonso Fusco’s photos give us back the face of a city and its people. Still, they are also a cross-section of an era of man’s passage along the path of history in this part of the Gulf of Salerno, in a town with a prestigious history behind it.

A work that has been arranged by Claudia Bonasi for chapters, almost as if she wanted to accompany the reader on an orderly journey, without haste, able to offer, without smearing, a logical narrative thread. It is like the great European photographers (Sommer, Conrad) who came to Naples, no longer the capital of the Kingdom at the dawn of photography.

However, an attractive city for great travelers: the street, the boundless theater of a people engaged in an existential gesture, ignited their imagination of “foreigners,” who impressed on photographic plates the instant stolen from time. And so it was for Alfonso Fusco, who, with his daily work, has given us a picture of how we were seventy years ago.