A Tradition That Heralds the Feast Day of the Patron Saint

by Vito Pinto | Cover Photo courtesy of Lello D’Anna

Among the many ancient southern traditions that have withstood the relentless march of modern life, and all the erasures it often brings, is the “raising of the cloth”. This deeply symbolic public ritual, observed exactly one month before a patron saint’s feast day, serves as a kind of sacred reminder. The Catholic Church blesses and raises a banner bearing the image of the saint to announce to the faithful: the time is near, the protector of your town, your village, your people is about to be honoured.

It’s a simple yet evocative rite. The parish priest, accompanied by altar servers and townspeople, processes with a painted cloth featuring the saint’s image to a chosen spot, often a symbolic or central point in the parish, where the cloth is raised high. There it remains, fluttering in the wind, visible to all until the canonical feast day. While this tradition may pass quietly in the cities, in smaller towns and villages, where community bonds run deep and everyone knows each other, it’s a moment of shared emotion and profound devotion.

A Sacred Banner for Saint John the Baptist

True to this age-old custom, Vietri sul Mare, one month before the 24th of June, raised its cloth in honour of Saint John the Baptist, the Forerunner and patron saint of this seaside town on the Amalfi Coast.

The banner was a double-sided painting by local artist Franco Raimondi, first unveiled to the public in 2021 alongside a newly commissioned painting of the saint.

In these works, Saint John, Christ’s forerunner, radiates prophetic power, calling out “Ecce Agnus Dei” (Behold the Lamb of God). But here, the Lamb is no longer cradled in the saint’s arms. Instead, the artist places it above him, resting gently atop the Book of the Prophets, watching over Vietri below, nestled at the saint’s feet. It’s a painting brimming with movement, as if Saint John himself is warning the enemies of faith to stay away from the land he guards.

Gelato: Vietri’s Sweet Sign of Celebration

And so, the raising of the cloth becomes a double celebration, of both the ritual and the new image of the saint. For many, this time of year brings back youthful memories, when the cloth’s appearance meant summer had officially arrived, and with it, gelato.

Back then, gelato was strictly seasonal. Unlike today, when it’s enjoyed year-round, in those days it was a true sign of summer. Every year, on May 24, Zi’ Pietro Cretella’s bar and gelateria “Centrale”, right in the heart of Vietri, would reopen for business, ushering in the warm season with its famous spumone.

This wasn’t just any gelato. Spumone was a work of art: a dome-shaped metal mould filled with layered gelato in different flavours, sponge cake soaked in liqueur, and a sour cherry in the centre. Once unmoulded, it was sliced into quarters and served, a multi-sensory delight. There was spumone with Sicilian cassata flavours, or with coffee, hazelnut, and chocolate, blended to achieve perfect balance on the palate.

And then there was the lemon spumone, made with the famous sfusato amalfitano lemons, paired only with strawberries. A taste of summer in every spoonful.

The Arrival of Summer on the Amalfi Coast

So, when Zi’ Pietro’s spumone returned to the gelato counter, and the cloth of Saint John rose above the town, summer had officially begun. And soon, so did the festivities.

Tradition held that the Notari family, owners of the once-prominent textile mill destroyed by the devastating 1954 flood, would decorate the main altar for the feast day. They would send cartloads of pink and blue hydrangeas, enough to bury the 18th-century altar in blooms. At the centre stood a large canvas of the Virgin Mary, flanked by Saint John the Baptist and Saint Irene, with the inscription: “Antonio De Rosa pinxit 1736.”

The Feast Day’s Eve in Vietri sul Mare

The night before the big day, the air would fill with a pungent, mouth-watering aroma: vinegar. It was the smell of milza, stuffed spleen, simmering in kitchens across the town. No home in Vietri would celebrate June 24 without it.

Dinner that night was a fixed menu for many: ziti or schiaffoni pasta with slow-cooked ragù, grilled steak over charcoal, crisp green lettuce, and of course, a generous portion of Zi’ Pietro’s spumone to finish. A meal for a saint.

“The Boys of Saint John”

Morning arrived to the sound of marching bands parading through the streets, waking the town with cheerful tunes. Over the years, many of southern Italy’s best-known bands were invited to play at the feast, accompanying the procession and bringing music to every corner of the town.

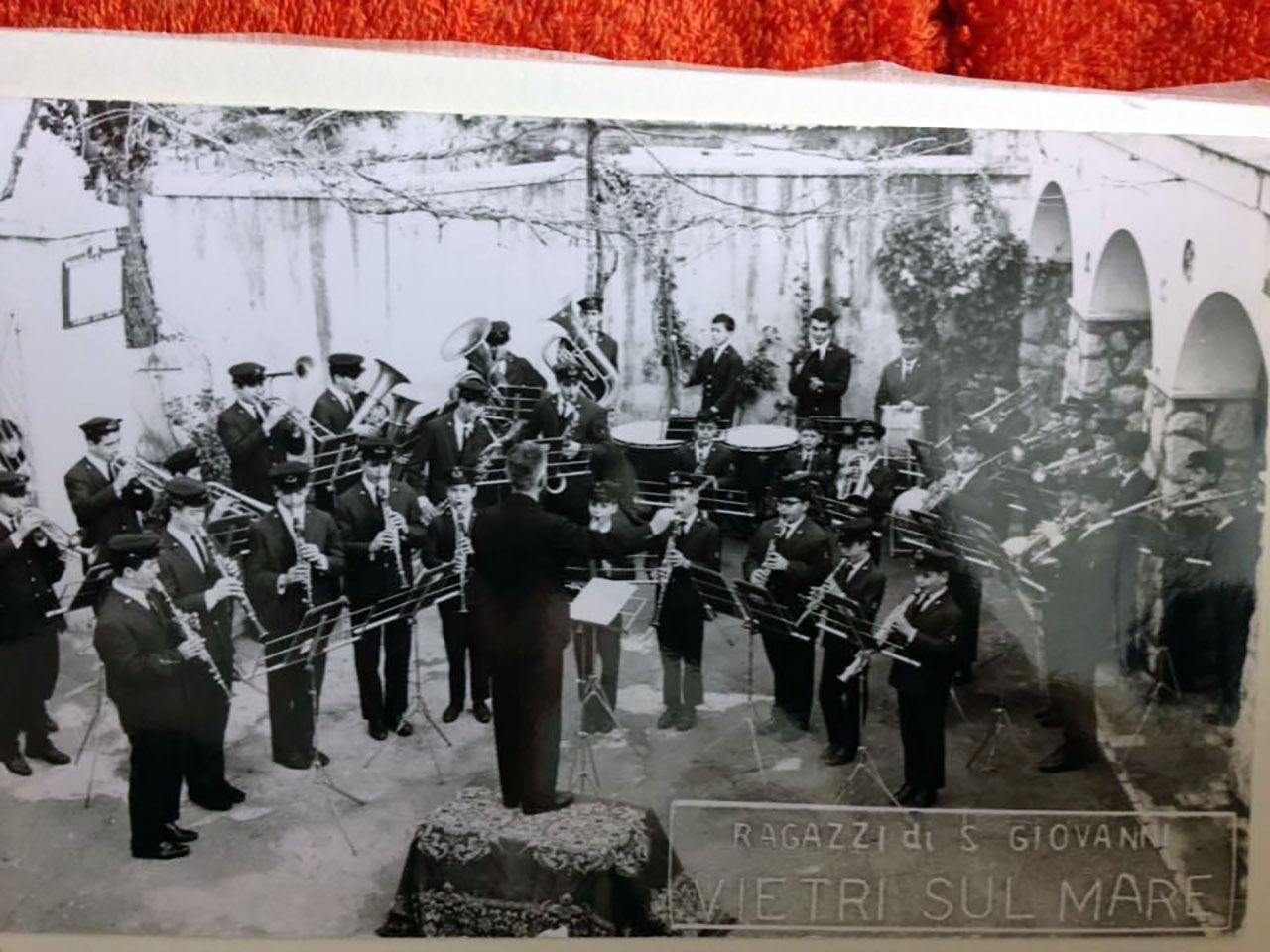

And then came “The Boys of Saint John”, a band made up of about fifty young locals from Vietri. They had all learned to play an instrument thanks to the efforts of Don Luigi Magliano, the parish priest at the time, and Maestro Antonio Avallone, who together founded the parish music school at the community centre.

Legend has it that Don Luigi personally signed dozens of IOUs to buy instruments for the boys. But it paid off: many of those students would later go on to earn music diplomas and become professional teachers. Their very first performance? On the feast day of Saint John, right in their hometown.

The emotion that day ran deep, not only among proud parents, but throughout the whole town. Vietri had its very own band: a group of young musicians who played for free at all the parish’s liturgical celebrations, just for the love of their community.

The Beauty of Simplicity

That feast day in the early 1960s remains etched in the hearts of many in Vietri. There they were, young boys, beaming with pride, playing joyful marches as they accompanied the saint through the streets. That evening, the crowd swelled for the closing concert, and as always, the celebration ended with a blaze of fireworks lighting up the night sky.

You might say it was all very simple. And you’d be right.

But that’s exactly how things used to be, simple, genuine, heartfelt, untouched by technology or spectacle. In those days, everyone knew each other, sometimes too well, and your neighbours were practically family. That was enough. A small community, a few joyful rituals, and a deep love for tradition.

And really, what more could you need?