A career that arrived by chance that led him to tell the story of life in images

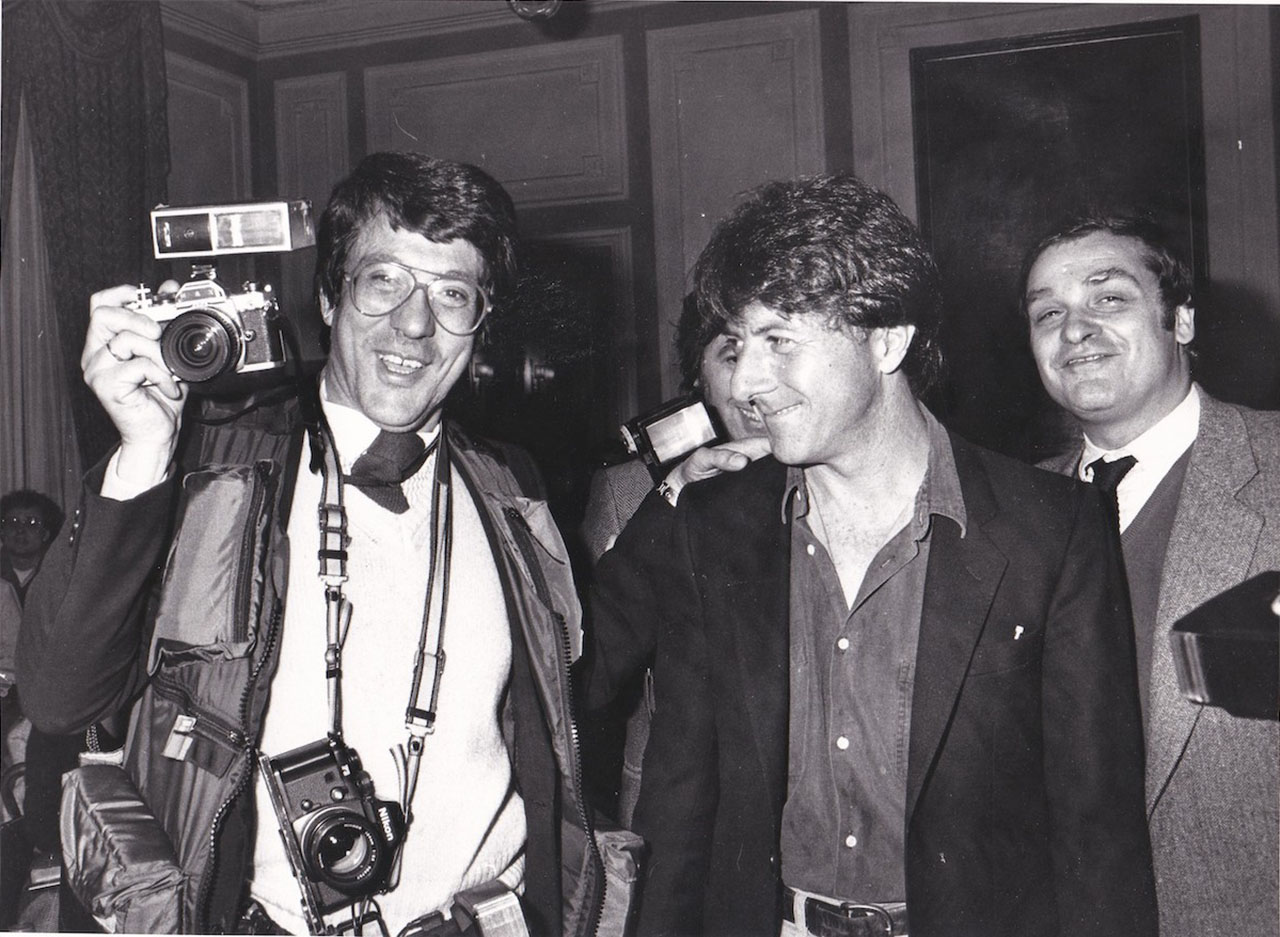

July 14th, 2021.By Vito Pinto, photo by Massimo Capodanno

The chronicle of an ordinary social everyday life is frequently sprinkled with events, The telling of which is often more effective with a photo than with an entire journalistic article. Suppose one looks at the century that has just passed, defined as “short” but intense and dense with happenings. In that case, one is left with bated breath in front of photos, strictly in black and white as a crown of emotions, that narrate, consigning to history, scenes of ordinary human folly.

One thinks of the 1980 shooting down of the DC9 Itavia over the skies of Ustica, the 1981 attack on Pope John Paul II in St. Peter’s Square, or the 1982 attack on the Synagogue Maggiore in Rome. Not forgetting those related to the 1980 Irpinia earthquake, the 1983 visit of Pope Wojtyla to his attacker Mehmet Ali Ağca in the Rebibbia prison in Rome, or the 1984 visit in which President Pertini on the deck of the ship Vittorio Veneto welcomed Italian soldiers returning from the mission in Lebanon. Events have marked our daily history, many of which have been consigned to history by Massimo Capodanno‘s photos.

The relationship with Positano

Roman by birth, 76 years old, Capodanno recalls, “My parents at the time of my birth were in Lisbon, where my father was an official at the Italian Embassy in Portugal, but my mother returned to Rome to give birth because her father wanted to see his grandson.”

Hence the long tale of life as a photojournalist lived with intensity. He began frequenting Positano in ’72 after meeting his wife, settling permanently in 2007, when he retired after 34 years at the ANSA news agency. Almost over-enthusiastic, he says, “I like Positano very much, but it is tiring to live in. To buy a pack of cigarettes, I must climb 110 steps.” And he brings to mind Nobel Prize winner for literature John Steinbeck when back in 1954 this vertical town he wrote, “Don’t walk if you go to see a friend: you climb, or you climb down….“

A chance beginning

To photography, Capodanno came “by chance,” as he points out during a chat with us in his Positano home overlooking that corner of creation where, about Domenico Rea, “God, on the day of creation, did not forget a single detail.” He was drawn to painting and sculpture and moved to Milan for a job as a graphic designer, but found himself a photographer in an art gallery for artists’ “vernissages.”

In ’69, he moved to London, assisting fashion and advertising photographers such as Mark Hamilton and Duncan Willet. But when Germana Marucelli, a Florentine fashion designer with an atelier on Corso Venezia in Milan and founder of the “San Babila” poetry prize, a friend of his mother’s and in whose Milanese home he was a guest, sold some of his photos to “Vogue” magazine, Massimo realized that was the way to go.

His return to Rome saw him working in the press office of RAI, “Il Fiorino” and “Il Messaggero,” for which he produced reports on entertainment, politics, and current events. Then in 1973, he was hired at ANSA, and here began his adventure around the world. He recalls, “I saw all the Mediterranean countries except Turkey. I’ve been to so much of Europe, I haven’t seen Russia and Communist China, but I’ve been to Taiwan for Miss Universe … expensed everything.”

Mobile radio

Looking at his photographic (or life?) archive, one realizes that at crucial moments in the news in human history, he was there. Spontaneous question: how did he do it? He smiles, Maximus, then, “Planes trains, cars. I had a Rover, and I was going flat out. And I had a little radio on board with which I listened to “double sail 21,” the police radio.”

He points at me with his eyes that have seen so many and adds, “It was not a crime because it was a mobile radio, and then both the police and the carabinieri knew I had this contraption.” Indeed news reporting, which in journalistic jargon is called “crime reporting,” is, in many ways, fascinating but also complicated.

Says Capodanno: “The early days were problematic, hard, then the officials, the officers of the carabinieri began to know me, and so sometimes they would call me when there was something important. To this day, I still talk to them over phone”.

From show business to politics

Before blackness, the “old” photojournalist points out that he had been in theater, television, art, and film, all fields that were too narrow for him: too static for his dynamism, his not knowing how to stand still, so much so that even today when he moves he always carries his camera with him.

“You never know what you might run into. Photography is also sometimes luck, a fluke.” And then there was politics and his “privileged” relationship with Craxi, “he often called me to get my photos,” with Pertini, who admitted him to a specific privacy, as long as he was quiet. Andreotti, who one day in Syria, where he had gone to meet Assad, told him, “You’ve ruined me. You’ve realized Forattini’s dream.”

The humanity of the photojournalist

There was also a time when he had been destined to follow Pope John Paul II, but on that day of the bombing in St. Peter’s Square … Massimo was not there. Someone further up in the newsroom had destined him to cover a political rally in Piazza del Popolo, a rally that “I hated with all my might, as I still do today with those who made me go to that rally instead of letting me do my work in St. Peter’s Square.” Massimo recalls that he knew the papal security officials, so he would have done exceptional service.

And the regret is evident, even today, in his voice. It lingers in his mind after “bitter” memories: “There is one photo that looking at it still makes my heart weep. To never have been able to recognize the subject, to identify that corpse floating on the sea at Ustica. It was a woman. I also asked friends in the Navy, but they could not give me an answer.”

In the face of this sensitivity, this deep humanity of the photojournalist, those verses of his that also won him a literary prize bounce to mind: “I would like to hover free and light in the sky / to twirl and then fly swooping toward the sea / to catch a fish to give to my chicks. / I’d like to fly far away to other skies / other seas and shores. / I’d like to fly away with you / and build in other rocks our nest …”

One wonders how a poet can tell the crime story, “It’s the work of every day, of the photographer and the Agency.” Black and white work to enhance facial feelings, emphasize emotions, and the drama of events. Then with the 1990 World Cup, color photos were required, so ANSA began to work with color.

Tomorrow’s photo

But Massimo still likes black-and-white and does not disdain it. When he can, he enhances it. To look at him sitting behind his desk, a clipped corner overlooking endless Positano, his storytelling, even about the dangers he encountered, seems like a movie narrative.

This fiction has a real impact when the reporter opens his computer and begins to show the photos: the archive of memory, the treasure chest of life, and the book of history. And he remembers the dramatic moments when they were taken, the dangers he faced. Once, he even risked being shot. It was when Carabinieri was looking for terrorist Natalia Ligas. Massimo had hidden in a bush.

When they discovered him, he had to shout that he was a photojournalist and was saved because one of the ROS recognized him, “He’s the one from ANSA,” he said. Asked if he had a photo he would have liked to take, a suspended photo, he replied, “That’s the one I’m going to take tomorrow.” To remind him of the numerous awards he has received, he replies, “Someone remembered me.” But a question urges: would you do the life you did again?: “All of it, even now I would go, even if my legs don’t help me as much anymore.“