Thanks to the work of artisan papermakers, the precious sheets continue today, as they once did, to tell the story of one of the world’s best-known coastal traditions.

May 1st, 2022. By Anna Volpicelli

A series of paper mills paraded along the Ferriere Valley and the town of Amalfi. Whole families of artisan entrepreneurs were busy developing and perfecting one of the arts, which, even today, fascinates the world. The prized Amalfi Paper turned one of Italy’s Maritime Republics into the most dynamic and innovative center of production in the 13th century.

The industrial revolution and the 1954 flood that destroyed part of the paper mills led to a slow decline in this activity. However, today there are still families that continue to innovate and spread this ancient and, at the same time, current tradition. Beloved by collectors, publishers, artists, and even the Vatican-it appears to be the official paper of the Church State-the Amalfi paper continues to be praised nationally and internationally.

History

No official documents attesting to the birth of the first papermaking plants. Still, it is assumed that it was around the 12th century when Frederick II, with decretal norms published in Melfi, imposed a ban on the use of “bambagina” (paper made from a pulp composed of hemp and flax) by the curials of Naples, Sorrento, and Amalfi in published acts, urging the populations to continue to use parchment.

An art of papermaking that the Amalfitans learned from the Arabs, given the trade relations they had with the East and because of the presence, probably, of fondachi in foreign lands.

Success

Over time, production intensified so exponentially that Mill Valley saw numerous paper mills proliferate. The nature reserve was the strategic location for these small industries thanks to the presence of the Canneto River, which through the mills and a series of underground canals that ran under the paper mills, supplied the water necessary for the papermaking machinery.

By 1700, the actual explosion of this craft activity, there were as many as 11 paper mills in Amalfi alone. It brought a growth in the economic wealth of the papermakers to such an extent that they founded the Congrega dei Cartari, a kind of cooperative that had its headquarters in the Church of the Holy Spirit, bordering the Valle dei Mulini, a productive area.

Production

But how did the creation of paper take place? What was its production process? Raggs and cotton cloths were used to make the various sheets the yards bought from the various rag merchants. Such fabrics were placed in special tanks, called piles, where they were shredded and turned into a kind of pulp through a series of wooden hammers, at the end of which iron nails were placed. It is said that the shape and size of the nails determine the texture, weight, and thickness of the sheets.

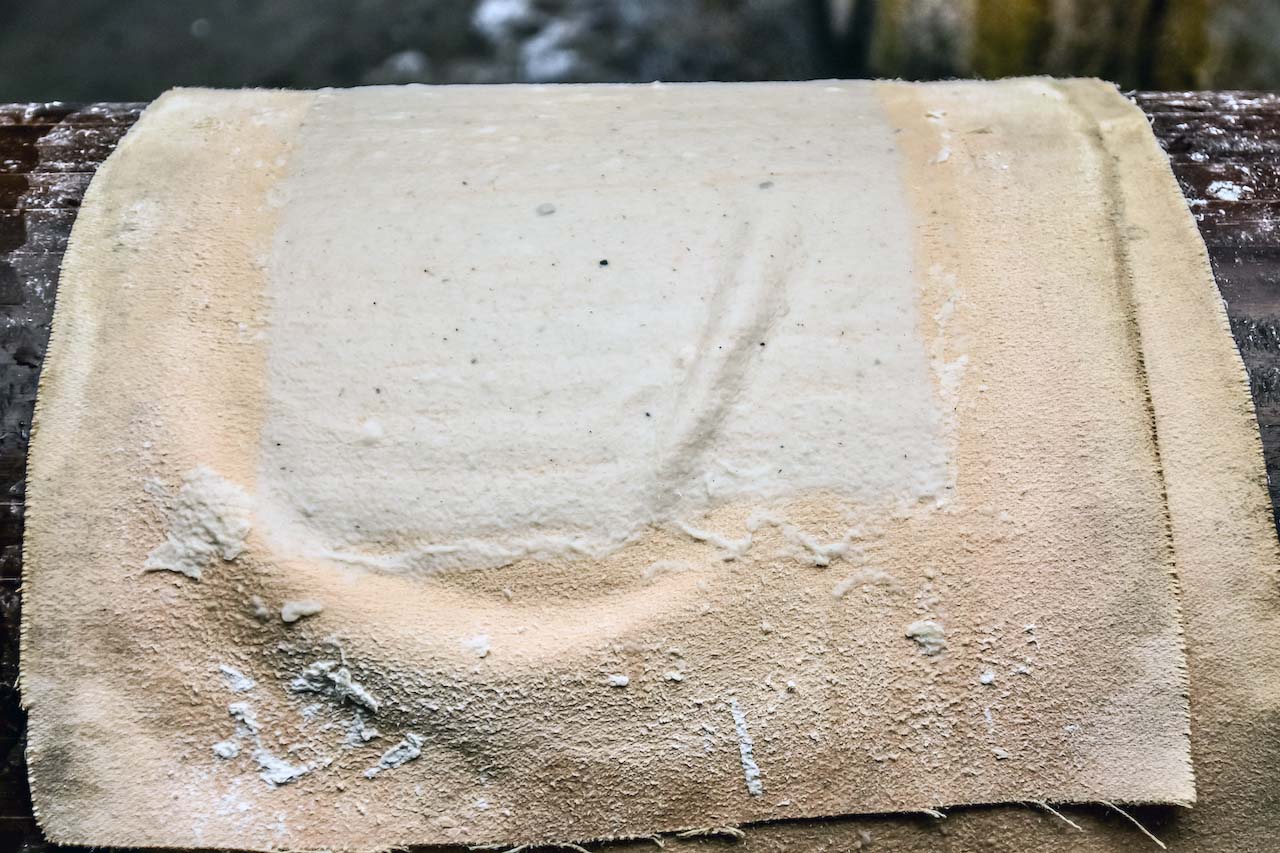

Such machines were driven by the force of water, which precipitated on a wheel set into action a drive shaft called a spindle. The pulp created by the machinery was then collected and placed in a masonry vat, a round basin. Here with a kind of oversized wooden spoon, the mash was stirred, at which point a sieve-like instrument was dipped, on which was affixed the watermark, the seal or symbol of the family, on which a layer of paper was formed, which was then poured onto the felt, which gave life to the first sheet of paper.

Sheet after sheet, needing about 40 to 50, the “stack” created was taken out and passed under a press for water absorption. From there, it was drying, and the sheets were hung on spreaders. In 1745 the wooden-mesh machine was replaced by the Dutch machine, which made it possible to speed up and perfect the entire process.

The Paper Museum Foundation

Today, machinery and manufacturing processes are seen inside the Paper Museum Foundation, founded by Nicola Milano, a descendant of a generation of papermakers. Milano was one of the Amalfi Coast’s most outstanding paper entrepreneurs, who, after his father’s death, at the age of 13, managed to carry on the three paper mills owned by the family.

Today, the museum is housed in an old paper mill owned by the Milano family dating back to the 14th century, and is located in the town of Amalfi, on the road leading to Valle dei Mulini. On display inside are centuries-old tools and machinery used to produce paper by hand. Here, trained guides accompany guests on tour, demonstrating how the whole process took place. It is an experiential workshop where trying some of the processing is possible.

Outside the museum is a reproduction of the spreaders and an area dedicated to channeling water from the Canneto River, which is used to activate both the wooden-mesh machine and the Dutch machine in the museum.

The Amatruda family

One can only talk about the history and evolution of Amalfi Paper by mentioning the Amatruda family, whose paper mill is still active and known throughout the world. A producer for centuries, after the 1954 flood that destroyed most of the paper mills, the tenacity and passion of Luigi Amatruda, Amalfi’s master papermaker, did not give up and, with determination, managed to keep part of the business alive by returning to traditional methods of processing through the use of cotton.

“My father,” says Antonietta Amatruda, a professor and manager with her sister and the whole family of the paper mill in the Valle dei Mulini, “was animated by a great love for this work. His mission was always to keep this activity, this art, alive for the family, the entire town of Amalfi, and the entire coastal territory.” The paper was used for the printing of several influential publications, including Hugh MacDiarmid’s A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, at the behest of the distinguished publisher Mardersteig, printer of Gabriele d’Annunzio, The Aeneid from Edizioni dell’Elefante, Petrarch’s Canzoniere, printed by Marotta, and Shakespeare’s Hamlet, publisher Tallone.

Amatruda paper is not only used for the publishing world, but today its products range from watercolor paper to those for wedding invitations to notebooks and more. “Today, to take care of the paper mill, besides me and my sister Teresa, are my nephew Giuseppe Amatruda, my children, and my brother-in-law. We try to do it with the same passion my father passed on to us.”