A journey into one of the most world-renowned arts, an expression of the excellence of the Amalfi area

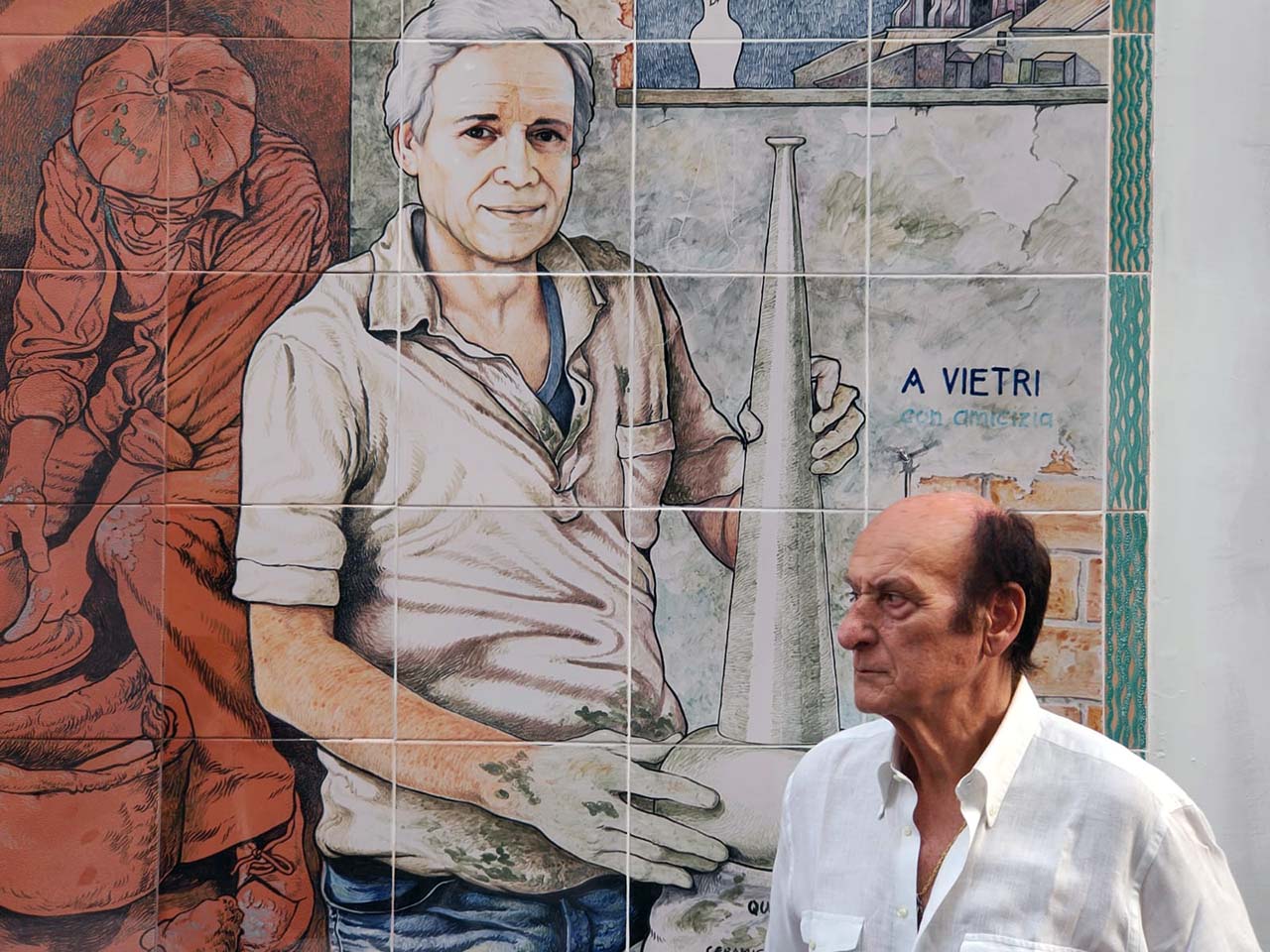

June 6th, 2023, by Vito Pinto

On red embrici and rare high terraces rises the majolica-tiled ambrogette dome of the church of San Giovanni Battista in Vietri sul Mare, set overlooking a sea enclosed between the two bights of the Gulf of Salerno where history has walked along with myths and legends.

An ancient history that harks back to the Etruscan Markinna, “a Tirreni condita,” wrote the geographer Strabo, a prosperous city flourishing with trade and commerce, destroyed by Genseric’s barbarian hordes and from which was born Veteris ad mare. The diligence of the Vietrese people has unfolded throughout the centuries with industrial factories, gualchiere, textile settlements, paper mills, shipyards, and craft workshops that developed and increased a civilization made of clay.

The first votive shrine on the Amalfi Coast.

The earliest traces of ceramic craftsmanship are found in faded documents, while evidence of artifacts that still exist date back to the 17th century and especially to that 1627, the year with which is dated the oldest evidence of a votive aedicule still living on the outer wall of what was once a tower at the hamlet of Raito: it depicts a Christ on the Cross between St. Anthony of Padua and St. Francis of Assisi.

But even earlier, in the late 1500s or early 1600s, it was dated by Prof. Venturino Panebianco, the late director of the Provincial Museums of Salerno. The votive plaque represents the Baptism of Jesus by John in the River Jordan, owned by Dr. Giuseppe Di Costanzo in Marina di Vietri, which went missing perhaps in the tragic flood of 1954.

Only a black-and-white photographic representation of that plaque exists, taken in 1935 by photographer Ernesto Samaritani and found in the Provincial Museum of Ceramics archives in Vietri sul Mare.

The debate over authenticity on the Amalfi Coast.

In the article “La maiolica d’arte di Vietri sul Mare,” Prof. Panebianco thus wrote: “Another votive tile, now owned by Dr. Di Costanzo in Marina di Vietri and representing the Baptism of Jesus, although undated, seems rather referable to a local workshop of the 1500s: and, apart from the typically Vietrese technique, it is also a specimen worthy of a particular regard for vigor and conception.”

Panebianco’s dating, however, disagreed. The historian Andrea Sinno, who, in his book “Trade and Industries in the Salerno area from the 13th to the beginning of the 19th Century,” wrote thus: “Dr. Di Costanzo’s tile is equally to be attributed to the brush of a master, who mastered the new Abruzzese art and wanted to give an essay of his exquisite artistic qualities when in this city the new art was beginning to arise.”

And it was, thus, credited to the thesis that wanted ceramic art in Vietri sul Mare brought by masters from Abruzzo and especially from Castelli, a city of ancient ceramic tradition.

The Byzantine imprint in Vietri sul Mare.

Subsequent studies and in-depth studies suggest, however, that pottery in Vietri was brought by Byzantine monks who had their stronghold in the convent of St. Nicholas of Gallucanta located high up at the foot of Mount Buturnino (San Liberatore) dominating Salerno below, as is evident from quite a few documents collected in the volume “The Parchments of S. Nicholas of Gallucanta (9th-12th centuries)” edited by Paolo Cherubini, papers that, among other things, report earthenware vessels called “tafareas,” a term indeed over time corrupted into the dialectal “scafarea,” an object for daily use known to be made of glazed earthenware and sometimes decorated in the concave center.

The export of ceramics from Vietri sul Mare.

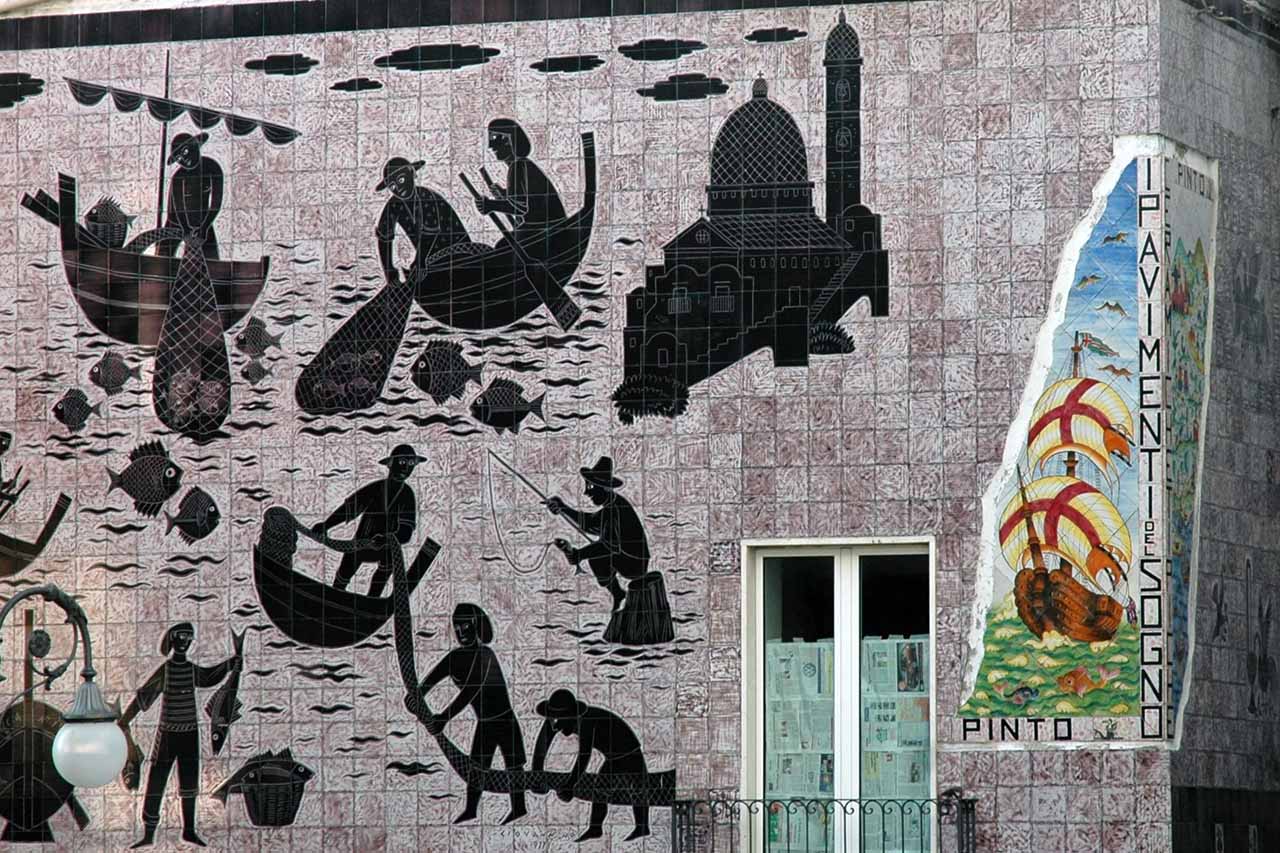

An activity, that of ceramics, which over the centuries first coexisted with other local businesses and then established itself as a vital activity of the area, exporting to Sicily and some countries of the Mediterranean belt of Africa, its products, mainly objects for everyday use (the Sicilian “robba”) and tiles, the “riggiole” for short, characterized, the Vietrese ones, by the peculiar format of cm.19 x cm.19.

Vietrese expansion in Sicily

In the volume “Ceramica Siciliana d’Arte,” editor Antonino Ragona, at the time Director of the Regional Museum of Ceramics in Caltagirone, wrote:

“On the markets meanwhile flowed in considerable quantities Ligurian and Neapolitan ceramics, especially from the respective centers of Albisola and Vietri. It was mainly pottery destined for aristocratic canteens and pharmacies. The ports of Palermo, Trapani, Sciacca, Syracuse, and Messina also penetrate the island’s interior. They are imitated especially by the workshops of Caltagirone, which also produced eighteenth-century pottery and apothecary ware on par with those of Trapani. With vase production, Vietri also had majolica tiles flowing into the island, which soon supplanted Palermo’s production. This encroachment of continental majolica favored in the second half of the eighteenth century the rise in Malaspina, a pleasant district near Palermo, of the glazed earthenware and majolica factory was founded in 1760 by Francesco Oneto, Duke of Sperling. The workshop, directed by Palermo potter Calogero Pecora, gave good essays, but, as a thing born of the will and initiative of a private individual, it closed in 1780 as soon as the promoter died.”

Cultured pottery

And here, a point is made about the production of Vietri ceramics, which was not only a production of everyday objects (caponcelli, plates, cups, glasses, and anything else belonging to this production sector) but was also composed of a certain “cultured” ceramics made of “pump plates” for the tables of the nobles and majolica tiles for floors and walls.

In addition to the floor of the Galleria degli Specchi in Palazzo Valguarnera-Gangi, where is the splendid Vietri ceramic floor with the representation of the gattopardi and where the dance scene in the film “The Leopard” was filmed, in Palermo there is also another noble palace and a convent where there are large rooms with floors made in the workshops of Vietri sul Mare.

Testimonies tell of the productive and economic vitality of our coastal center, which never stopped producing majolica for daily use, but also votive plates, today representatives of powerful popular devotion and unique examples of a centuries-old activity.

A phenomenon of innovation

There has certainly been no shortage of periods of fatigue. Still, there is always some fine example of ceramic work, signed and often dated to declare a presence that today is the most extensive in the production sector, along with predominantly summer tourism.

After the period that should rightly be identified as the “Central European period in Vietri ceramics” (and not erroneously “German”), during which a colony of foreigners added a further cultured figure to production, one for all the Polish Irene Kowaliska alongside local artists such as Guido Gambone, Giovannino Carrano, and the Procida brothers, the coastal town was a ferment of innovation.

A unique partner along with Faenza in the proposal and then transformation into a law for the protection of art and traditional craft ceramics, Vietri has been one of the ceramic places where the ferment of ideas has been alive, not stopping at the simple reproduction of ancient and established decorative patterns, but always traveling the paths of innovation.

Contemporaries

Active witnesses are those young people of the 1960s who, in the silence of the Vietri workshops, operated an evolution by innovating forms and chromatic signs. Carmine Carrera, with his dozens of forms pulled at the potter’s wheel, Giovannino with the instinctively cultured stroke of his representations, Guido Gambone with his “partner” Andrea D’Arienzo, who stood out for new glazes, laboriously and stubbornly researched, and new ceramic frontiers, Giovanni Cappetti with the uniqueness of the floors with an ancient design but with a modern stroke, the “Vietri Group” formed by Autuori-Collina-Ferrigno, young people who were bringing a breath of fresh Mediterranean air, seeking new paths and opening them to young people, one thinks of the Liguori brothers and Francesco Raimondi, who were following the path of craftsmanship, making it more and more cultured. A ferment of ideas, proposals, and new horizons was thus being opened wide to Vietrese ceramic solarity.

Inclusion in hotels

A path that, in some ways, continues and, at times, becomes a proposal for tourist hospitality, such as the case of the Mendozzi family, hoteliers in Vietri sul Mare, who embellish the rooms of their hotel located overlooking the vast gulf, with the colors and signs traced by local master ceramists, proof of a union between ceramics and tourism that in recent years has become a winning combination for the Vietrese economy.

Indeed, for this sector to continue on its path, continuing to build its centuries-old history, it needs new stimuli, new energy, and above all, the proper support of those who are in charge of protecting and supporting the interests of their country; we are talking about those local administrators who are often distracted by other sirens, whose sole purpose is to run the ship into the rocks.

Comforting, however, and in some ways, is the ever-increasing misappropriation of the term “Vietri ceramics”: a message that is flattering in its desirability but misleading and should be appropriately refuted. The ceramic identity of Vietri sul Mare is the community’s heritage that has been practicing it for centuries.

The constant transmission of a craft

For more than five centuries, uninterruptedly, clay has been worked, glazed, and decorated in Vietri sul Mare, a history of ancient, artisanal, authentic knowledge is perpetuated where each object is born solely from the hands of man and woman at the potter’s wheel or at the color banquet, to bring a unique and unrepeatable thing of Mediterranean history into homes.